RBGPF

0.0000

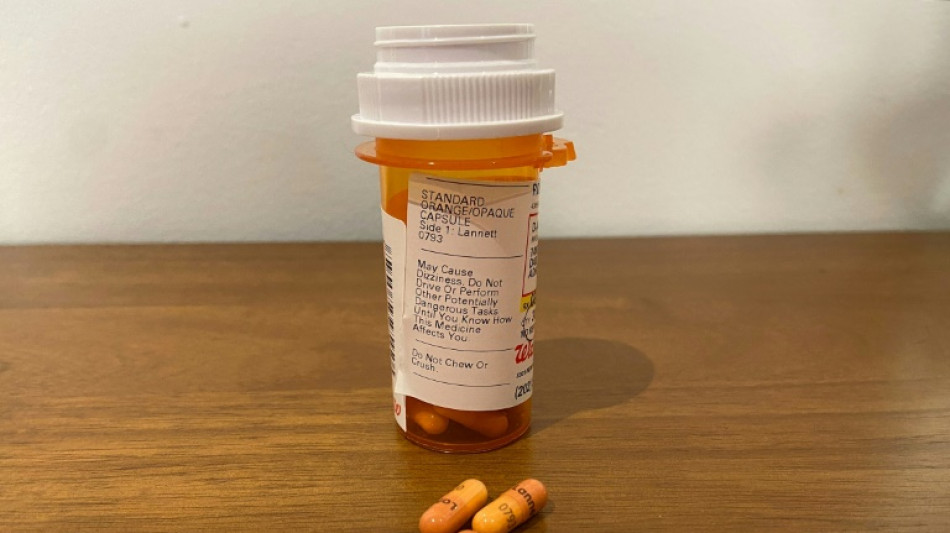

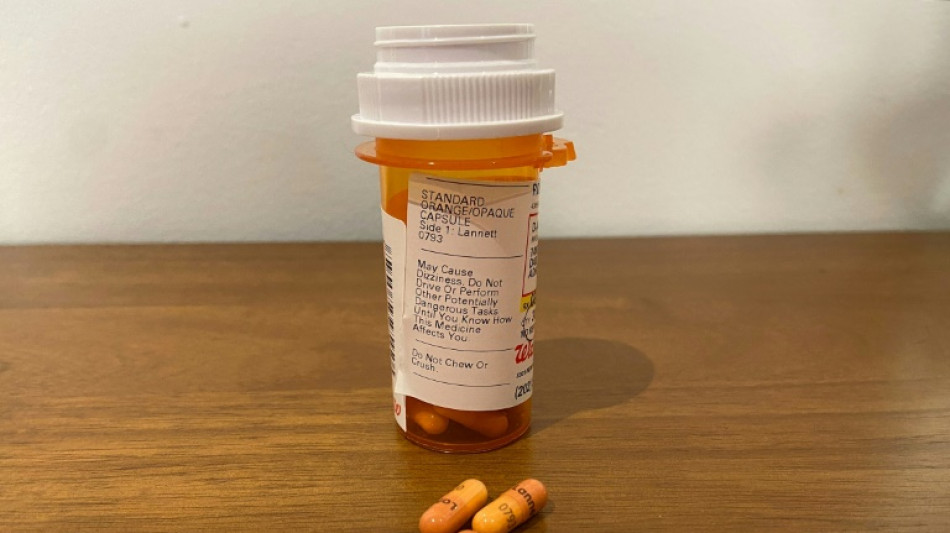

Adderall is an effective treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but a sharp rise in US prescriptions over the past two decades has sparked concerns among researchers about rare but serious side effects.

In a striking new study published Thursday, a team led by psychiatrist Lauren Moran of Mass General Brigham in Boston found that individuals taking high doses of the stimulant face more than a fivefold increased risk of developing psychosis or mania.

Key factors include the lack of upper dosing guidelines and the notable increase in young adults using the medicine since the Covid-19 pandemic, driven in large part by the rise of telemedicine providers.

Moran told AFP her interest grew from her time at a hospital inpatient unit treating college students in the greater Boston area.

"We were just seeing a lot of people coming in without much of a psychiatric history, developing the first episode of psychosis or mania in the context of using prescription stimulants," she said.

When the Food and Drug Administration became aware of such cases in the 2000s, it added a warning to the drug's label -- but relatively little research had been done to quantify the rates of side effects or how they related to the dosage level.

For their investigation, Moran and colleagues reviewed the electronic health records of people aged 16 to 35 admitted at Mass General Brigham hospitals between 2005 and 2019. That is the typical onset ages for psychosis, or losing touch with reality.

The researchers identified 1,374 individuals experiencing their first episode of psychosis or mania -- a disruptive state characterized by high energy, erratic behavior -- and compared them to 2,748 control patients who were hospitalized for other psychiatric conditions.

By analyzing Adderall use during the previous month and adjusting for other variables like substance use, they were able to specifically determine the impact of stimulants.

They found those who had taken Adderall were 2.68 times more likely to have been hospitalized with psychosis or mania compared to those who were not -- and this increased to 5.28 times more likely at higher doses of 40 milligrams and above.

A separate analysis found no increased risk with Ritalin, another stimulant prescribed for ADHD. Moran suggested this could be due to key differences in how the two drugs work.

- Telemedicine companies -

Both medications raise dopamine levels, a chemical messenger involved in the brain's reward system, motivation, and learning. However, while Adderall, an amphetamine, increases dopamine release, Ritalin works by blocking its reabsorption.

For Moran, a critical takeaway was the need for clear upper dose limits on labels. The current label recommends treating patients with 20 milligrams, but in practice, doctors vary widely in their prescriptions.

This variability partly stems from severe impairment in ADHD symptoms that require higher doses, but Moran has occasionally observed "carelessness in dose prescribing," while at other times, patients may "shop" for a doctor willing to prescribe what they want.

"People, including clinicians, might think they can eliminate all ADHD symptoms, but that's not a realistic expectation," she added.

Telemedicine companies, in particular, have come under scrutiny for allegedly overprescribing Adderall, contributing to shortages for those who genuinely need the medication.

The Drug Enforcement Administration, which had proposed revoking telehealth prescriptions for Adderall, extended them through the end of 2024 in response to significant public feedback.

X.Wong--DT